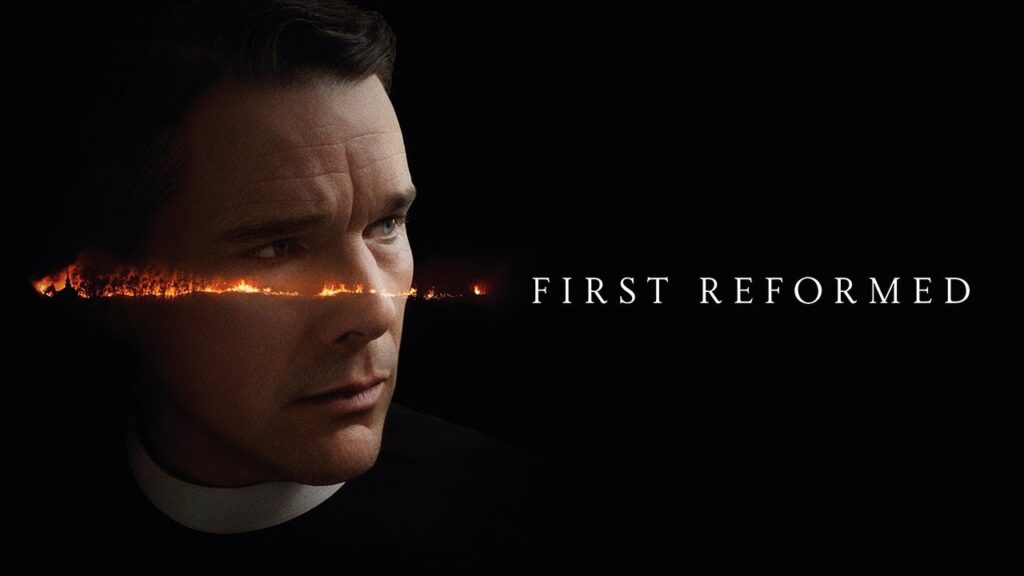

Film Analysis: First Reformed (2017)

First Reformed is a film that deals masterfully with the themes of guilt, despair, and hope, especially within a faith context. It portrays how we can internalize guilt—for our own action, inaction, or even for the actions of those around us—and how this can drive powerlessness and hopelessness. It also powerfully demonstrates how hope can be the remedy of despair and how it is hope that persists even in the face of despair that is the most powerful. The film helps us recognize that the ideals of a perfectly just world and a moral life do not and cannot exist to their fullest extent in the present. However, it asserts that faith demands that we hope for and trust in them regardless, and it is this hope which can sustain us in the bleakest darkness.

Ernst Toller is a man running out of hope. He pastors a vanishingly small Christian Reformed congregation at a centuries-old New England church. He lives alone, bereaved of his son and abandoned by his wife. His health is declining drastically, and he has resigned to let it run its course. He also can no longer muster the strength to pray.

A casual onlooker may discern little difference in how Reverend Toller conducts himself publicly. He still dutifully performs his pastoral role each Sunday and even does small repairs around the church, guides its historical tours, serves in the community, and counsels his congregants throughout the week. However, it is when we follow Toller into the solitude of his empty house, witness his excessive drinking, and lend audience to his narrated journaling that we perceive the dark inner life of a deeply troubled man. The depiction of depression, from the outside and the inside, is a compelling one.

The central themes of the film, as well as the objects of Toller’s struggle, are introduced within the first twenty minutes in a counseling session with a 30-year-old man from the church. The man’s wife, Mary, asks Reverend Toller after the service to talk to her husband, Michael, who is struggling with his own depression and wishes to terminate the couple’s pregnancy. Toller meets with Michael in the couple’s home and learns the source of his sorrow. He is part of an environmental action group and has become obsessed with the movement and his belief that, quite literally, the end of the world is near. The room they meet in testifies to his zeal for the cause: a doomsday projection plays on a screen in the background, displaying a decades-long trajectory of global warming, and the wall is adorned with pictures of activists martyred while defending nature. Michael asks Reverend Toller if one can sanction bringing a life into a world that, within three decades, will be decreasingly viable, several degrees warmer, and devolving into chaos.

The nature and content of Toller’s response are revelatory of both his psyche and the film’s core tenets. Toller accepts Michael’s fears and despair as legitimate, but he asserts nevertheless that they are not sufficient cause for giving up hope. Instead, a righteous and faith-driven life must choose hope over despair. Appealing to the authority of his own experience, Toller relays how both he and his father had served in the military and how he had encouraged his son to do the same despite his wife’s opposition. Tragically, Toller’s son lost his life six months into his deployment, and his wife left him as a result. When Michael asks how Toller was able to go on, he replies:

“Courage is the solution to despair. Reason provides no answers. I can’t know what the future will bring. We have to choose despite uncertainty. Wisdom is holding two contradictory truths in our mind simultaneously: hope and despair. A life without despair is a life without hope. Holding these two ideas in our head is life itself.”

Michael ponders this response for a moment, then asks, “Can God forgive us for what we’ve done to the world?” Toller replies, “Who can know the mind of God? But we can choose a righteous life. Belief. Forgiveness. Grace covers us all. I believe that.”

Despite this response extolling hope for both the future and the possibility of grace, Toller himself exhibits lack of faith in either. In the scene immediately following their counseling session, he writes a quote in his journal from a monk named Thomas Merton: “I know that nothing can change, and I know there is no hope.” In reality, it is this sentiment which the minister has internalized even as he attempts to comfort Michael.

Toller discussed with Michael the “patriotic tradition” of his family’s military service. It was to maintain this legacy that he insisted his son enlist, and, as a consequence, Toller blames himself for the death of his son and the dissolution of his marriage. Now, Toller finds himself as a pastor at First Reformed, a church with a weekly attendance of less than a dozen and wholly dependent on the charity of a local megachurch called Abundant Life. In this dynamic, too, we observe a disconnect between an ideal of what should be and the reality of what is. Toller’s role as a Christian Reformed minister of a 260-year-old church (another nod to idealistic legacy) pales in comparison to that of Abundant Life and its lead pastor Joel Jeffers. Abundant Life has a massive building with a massive congregation, a huge staff, and ministries that reach youth, the homeless, and many others in the local community. Abundant Life is clearly thriving in terms of power, influence, and capital—a point driven home even further by its close relationship with local industrial giant Balq Industries. While Toller expresses respect and gratitude for Reverend Jeffers and Abundant Life, we cannot help but agree that it seems like “more of a company than a church” and a watered-down form of religion complicit with capitalistic pursuits and environmental destruction.

As the film progresses, Toller sinks deeper into darkness. Mary calls him urgently after she discovers a suicide vest hidden in the couple’s garage. Toller takes the vest, saying he will dispose of it and planning to discuss it with Michael at their next counseling session. However, instead of having the session in their home, Michael texts Toller to meet him at a local park where he has shot himself before Toller’s arrival—an added blow to Toller. Meanwhile, a massive celebration is being planned by Reverend Jeffers and Abundant Life for the 260th anniversary of First Reformed. In a preparatory meeting, Reverends Toller and Jeffers meet with a major sponsor of the event, Ed Balq of Balq Industries. After ordering apple pie (a subtle reference to Balq’s representation of American capitalism), Balq expresses his concern that the anniversary may be politicized, citing Toller’s recent officiation of Michael’s funeral which, as per Michael’s suicide note, had an explicitly anti-industrial and envrionmentalist message. Toller tries to defend himself as well as the environmentalist cause but is fiercely shot down by Balq to whom Jeffers quickly capitulates and defers. Surrounding these events, we see signs of Toller’s decreasing physical and mental health, worsening drinking, and growing obsession with climate destruction of which both Balq and, by extension, Abundant Life are complicit. As Toller struggles internally with his own shortcomings and those of others around him, his lack of care for himself takes on a bent of both surrender and self-flagellation.

Any help that might come his way, Toller pushes back against to varying degrees. Esther, a concerned member of First Reformed, continually comments on his health and urges him to take care of himself. Eventually, Toller harshly rejects her. In a conversation that becomes heated, Reverend Jeffers asks about Toller’s health but also rebukes him for inflicting guilt and consternation upon himself for personal failures as well as large-scale issues like environmental destruction. Jeffers claims Toller isn’t living in the real world and questions whether he has “any idea what it takes to do God’s work.” He follows this up by saying that he and Abundant Life are there to help. The issue with each of these cases is that neither Esther nor Jeffers can, on one hand, relate to Toller’s suffering or, on the other, share his recognition of the desperate reality within which they all live. Because of this, instead of helping him in his distress, their words and actions exacerbate his loneliness, guilt, and despair. The only presence in Toller’s life which can both commiserate with his suffering and genuinely help to ease it is that of Mary.

Immediately following Michael’s death, Toller asks Mary if she is an activist like Michael was. She responds that she shares Michael’s beliefs but not his despair. It is she who seeks out First Reformed, who requests counseling for her husband, and who does not want to give up her unborn child. Relentlessly, even while believing in the coming climate disaster and suffering the distancing and death of her husband, Mary does not lose hope either for herself or for her baby. She also becomes the one presence in Toller’s life that offers some true light and rest. After the suicide, Toller performs his pastoral duties outside the context of Abundant Life or First Reformed by comforting Mary and helping her take care of her home. As Toller’s hope grows dimmer and dimmer, hers remains constant. The film culminates with Toller’s obsession with the world’s evils growing, his faith in the church as a remedy lost, and his will to live killed. He insists that Mary not attend the First Reformed anniversary celebration, planning to strap on Michael’s suicide vest and bomb the event. However, as he is getting ready in the parsonage next door to the church, he is caught off guard and at a loss when he sees her unexpected arrival. He tortures himself by wrapping barbed wire around his bare torso, dons his clerical attire, and pours himself a glass of viscous drain cleaner to end his miserable life. However, just as he is about to drink to his death, Mary bursts into his home. He drops the glass, rushes over to her, and the two embrace and kiss to the movie’s end.

First Reformed explores the nature of despair and hope, and in so doing, posits two things. First, despair is driven by an utter sense that things are not as they should be—by the experience of sensing such a drastic disparity between reality and what one believes to be truly good, just, and beautiful that one is driven to a crippling hopelessness. In the case of Toller, this was felt in his broken family, the state of organized religion, his role at First Reformed, and the destruction of the earth, all made even worse by his internalizing guilt for the ills he saw in and around his life. Second, the remedy for such despair is continued belief in the truly good, just, and beautiful ideal—that it exists somewhere or will exist at sometime—and to retain this hope even in the face of the darkest of circumstances. It was Mary’s persistent hope that kept her from her despair and saved Toller from his. How much more distorted would even Toller’s own religious ideals have been had he, like Michael, given up, killing himself and many others in the process? Instead, it was ultimately Mary’s hope that shone a light into Toller’s darkness and saved him from it. Mary is a reminder that one can rarely escape despair on one’s own. Further, she is uniquely able to offer escape because she, too, has suffered and despaired. Mary shared Michael’s beliefs about the impending environmental collapse and suffered through his depression and suicide, yet she never wished to end her own life or that of her unborn child. She pursued hope by continuing to engage with Toller in her sorrow, she embodied hope through her life and pregnancy, and she became hope for Toller when all of his had run out. Sharing the name of Christ’s mother—and even bearing a child—she models both a practitioner of hope to be aspired toward and the salvific power provided by faith in the truly good, just, and beautiful, even in the face of suffering.