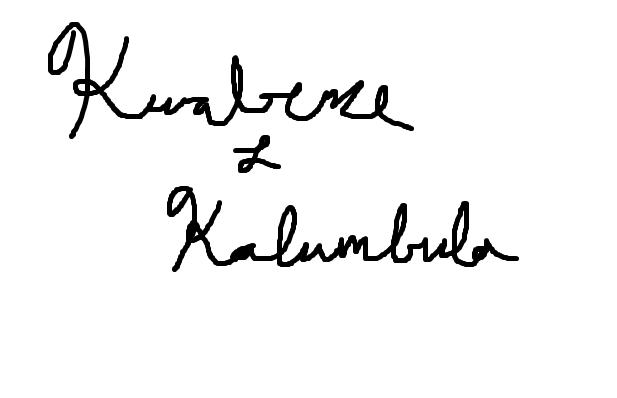

Kwabene in Kitindi

04. A Typical Sunday

Today was like a typical Sunday. The church service is scheduled to start each week at 9h00 juste, but I’ve never witnessed such a thing. This morning, we left our house around 9:25 to begin the fifteen-minute walk to the church. This entails exiting our front gate, walking down an uneven and sometimes slippery dirt incline about 30 yards to the road below, and following RN2 across the river towards town. Before entering the main part of the village, however, we take a right onto a side path. Some of the houses along this path are well-built brick houses with high metal roofs. The majority, however, are what I’ve come to recognize as the cheapest and most base-level homes. These have bare dirt floors and walls constructed from a lattice-work of branches stuffed with hardened mud. Instead of tin roofs, they have roofs of dried, thickly-woven leaves, and, from what I can tell, homes like these are smaller with just one or two rooms. Residents of several homes, whether brick or mud, are usually outside their front doors on Sunday mornings, either cooking or just hanging out. I greet them with a jambo (Swahili) or a samba (Kilega) as I walk through what would be their front yards on the way to church. I frequently get a big reaction when I speak Kilega to people, even though the only things I can say are “hi” and “how are you.” If they ask where I’m going, I tell them naenda kanisa and continue on my way.

After passing several such homes, we arrive at our church “building.” This is an open-air structure (pictured at the top) with a tin roof held up by several vertical wooden beams. It is these same beams that fill most of the space in the horizontal rows and which serve as our seats. They are not comfortable. Today, like most days, hardly anyone was there when I arrived with my cousin at 9:40—only less than ten kids and a few adults, including the man who usually presides over the service. He’d probably been there since 9:00, but most people arrived after me with some people not getting there until 10:20! Eventually, we were about 65 or 70 worshiping together in total. The majority of the congregation is made up of children. I would guess that they belong to the adults that are also in attendance, but it doesn’t seem like they necessarily arrive with them, so it is hard to tell. The rest of us today were 7 adult women and about 25 men. Most of the adults are faculty and staff from our school. Church attendance is mandatory for us and, though the location is not dictated, most of us choose to attend this church which my grandparents helped to plant. Because most of the school staff are men as well, I think this largely explains the gender gap; other men (and women) might not choose to go to church on a given Sunday, but because attendance is required for us, we’re there most faithfully. I suspect the rest of the disparity is due to gender roles—someone has to tend to the house even on Sunday mornings.

Mercifully (so I don’t have to spend too much time stiffening up on the wooden beams), a lot of the service is spent standing. It is also extremely participatory. Different members of the congregation are called on to pray by the presiding leader throughout the service. There are also times where all of us are called to pray together all at once (out loud or silently depending on one’s choice), and this is usually for several different topics in turn (the church, the school, the country, those around us who are sick, those around us who are pregnant, etc). The singing and worship take up a ton of time and are similarly congregation-driven. Anyone from the audience with the skill may choose to take the drum, and, instead of a worship team leading from the front like a concert, songs are led by someone among the congregation taking charge either from their seat or stepping into the aisle. Also, most worship songs are call-and-response, and everyone joyfully gets involved. They sing in at least three languages with which everyone in Kitindi is somewhat familiar—Lingala (most commonly spoken in western DRC, not here), Swahili, and French. I’m not sure if things are sung in Kilega because I can’t even tell Lingala and Swahili apart, but the French I can join in with. The whole thing is brilliantly and amazingly multi-lingual (much like most Congolese people) as well as intimate and communal. Check out a sample below!

After worship, there comes the reading of God’s Word, in both Swahili and French, followed by a sermon delivered almost entirely in Swahili. For everything up to this point, I attempt to participate. Since the singing is call-and-response, I conjure up some syllables that resemble Swahili, and I can usually understand the French. But once the sermon starts, I must simply endure. My attention drifts to farm animals that pass by (we had some pigs today, and a chicken made it halfway up the aisle!) or kids listening dutifully in their seats (or messing with each other or wandering around). These little ones are with us for the whole service, which is another aspect of church here that, like the communal participation and the open air, make the experience a deeply human* one. There is definitely an order and a structure to it; a ritual and a rhythm. However, children are not sent off somewhere unseen so that their parents can listen to the sermon, nor is the service itself hidden away from nature or from curious onlookers and passersby. Everyone stays together, and things are imperfect (just like people are). The service isn’t a product delivered from the front that the audience can passively consume. Rather, in lieu of amplifiers and instruments that can drown out our voices, a joyful noise is not raised unless all 65 of us raise it together. Several different members in the audience take the lead to play music or pray. And, I’m never quite sure when it’s going to start or when it’s going to end. All-in-all, I’ve found church services here to feel communal and natural and, again, human, as opposed to some of the more impersonal and consumeristic ways church can manifest in the U.S. Don’t get me wrong, there are many things I miss about church services and songs back home, and I most especially miss members of my church family, but I’m glad to be here now participating in this way with my local colleagues and to be able to relay this experience back home. We are truly all one holy catholic and apostolic Church. Que Dieu soit loué!

I will be an unpaid volunteer teacher at Union Academique de Kitindi for the 2022-23 academic year. Please consider giving as you are able by clicking the button below or addressing a check to International Berean Ministries and including my name on the memo line. Donations cover room, board, and travel expenses.

International Berean Ministries

PO Box 88311

Kentwood, MI 49518-0311

*A lot of my ideas about what being “human” means are derived from the theological anthropology laid out in the book You Are Not Your Own by O. Alan Noble. It’s a fire book, which I highly recommend for anyone looking for a helpful analysis of what’s wrong with “modernity” or who’s trying to be a healthy human (or raise healthy humans) in the 21st century.