06. On Death and New Life

According to ourworldindata.org, there are about 190,000 deaths and over twice as many births (385,000) per day around the world. Given my stage of life, I have tended not to experience close proximity to either. However, living in Kitindi means that the frequency of both occurrences is higher than I’ve otherwise experienced. The average lifespan here is about 60 compared to nearly 80 in the U.S., so death comes sooner to individuals and happens more frequently in communities. Additionally, as opposed to the 1.7 births per woman average of the U.S. (come on, folks, that’s not even at replacement rate), the average Congolese woman gives birth 5.8 times in her life (the third highest rate in the world according to wordpopulationreview.com). Besides simply the frequency of such occurrences, Kitindi specifically is a small town, where “everyone knows each other” in the colloquial sense, community is emphasized, and word travels fast.

The combination of these factors has brought to my attention two deaths that occurred last month and has also taught me some customs and procedures concerning births. The deaths were a bit removed from our immediate community—they were both relatives of members of our small, 60-person church. After the service on September 18, a throng of congregants left the service together to walk a short five minutes to the house of Willy Wasso Witte (or “W”), one of our church’s pastors who also happens to be the school’s chaplain, soccer coach, and a teacher of some courses in the social science specialization. I forget whom he had lost recently—perhaps it was an uncle. We gathered outside his low, mud-walled and leaf-roofed house, standing under the shade of a tree while he and his family sat among us, and then we began to sing. I do not remember the songs, nor did I understand them anyway, but at the time they sounded just like the other Swahili and Lingala worship songs we typically sing at church, including some of the theological words that I might recognize. As we sang, a shallow woven container, like one typically used to hold cassava or wheat flour, was produced, and everyone began making contributions to it: cinq cent francs here, mille francs there (about 25¢ and 50¢, respectively), three cassava root tubers, a bowl of brown beans, some rice. People reached for their pockets, or some others who had brought foodstuffs with them deposited what they had carried.

NOTE: I really wish I had a picture of this basket to share, but it seemed disrespectful at the time to take one, so I do not.

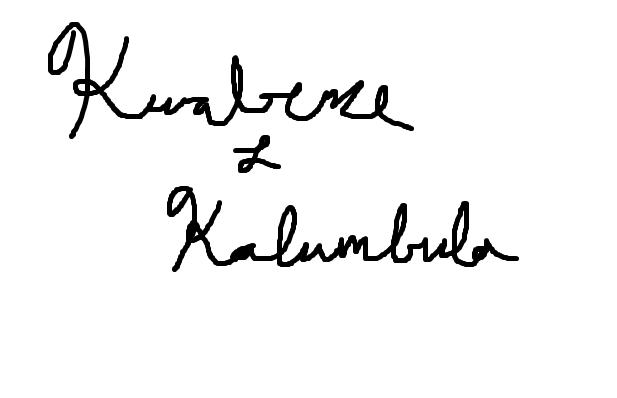

The next week, we repeated this visit with another household, this one being that of the only person I’ve ever met to bear my own name (Ghanaian Kwabena’s do not count—the etymology is different). Mr. Kwabene, too, was a former pastor of our church, now a congregant only, and I had met him in 2017 when I first visited Kitindi (and now teach one of his daughters in 7th grade). People refer to him as my homonyme or namesake, though my being called Kwabene has nothing to do with him. He himself wasn’t actually home when we visited to offer our condolences for the loss of his brother—he was in a different village, presumably that of his late sibling where other family members lived. Instead, we sang with his wife, again offering gifts to support the mourning family. In both instances, we visitors, mostly composed of my teaching colleagues, visited these homes not unhappily, but solemnly, dutifully, and generously in support of our community members, knowing they would do the same for us. Such are the dealings with death—at least in these cases, one-degree removed—among our church family.

All the while, my aunt’s pregnancy grew larger and larger in the month of September. I hadn’t seen a pregnant woman in a while, but she seemed due any day, though still going about household chores and teaching a few hours weekly despite it all. Henri had a conversation with her in mid-September which explained her size—she was expecting twins, some time in mid-October. Every day that passed worried us slightly, concerned and uncertain about how childbirth in a village like this would play out. There are two “hospitals” that I’m aware of, though I have entered neither and don’t intend to unless I have great need. Both buildings are single-storey and resemble what I would refer to as a clinic. I’m not sure how extensive their staffing and capabilities are, but we’ve had members of our extended household visit several times in the last month to treat malaria or other ailments.

Anyway, I was on a Facetime call with a friend (hi) over the weekend, when I received a text from my uncle. He mentioned his wife’s name and some words I didn’t understand, so I didn’t look closely until my call was done. It turns out that one of the words I didn’t get was French for contractions! He asked for prayer as Aunt Suzanna had gone into labor and was at the nearest hospital. Gloire a Dieu not three hours later, the twins were born! All went smoothly and quickly (gloire a Dieu again), and our extended household became a bit frenzied. Because of Bwami society rules (a hierarchical cultural and social structure of the Lega people), my uncle was not permitted to be present for the birth. Around 11pm when we began to hear shouts and whoops from his house nearby, Henri and I hurried over to join. Another aunt and a woman I didn’t recognize were excitedly dancing in the living room, preparing to bring sugar and other support to the mother and newborns. We congratulated our uncle and went back into the house to sleep, only to be awoken by more dancing and shouting around 2am.

On October 25, 2020, exactly two years from today, some friends from college and I made medium-term bucket lists. Mine included such items as “write and/or direct a film, short or otherwise” (done), “live in the Congo for one (1) year” (bet), and “have a child named after me.” At that time, I remember joking that those latter two could probably be done at once, and I guess the writers liked the idea. On Saturday, October 22, a girl and a boy were both born and named after “the most important guests of the year” —Carrie Anne (after my mother) and Kwabene. True homonymes indeed! Unfortunately, because of the hospital’s procedures to protect newborns, no visitors (not even the father) are permitted to visit until the patients are discharged, so I have not yet been able to meet Kwabene, though I dearly look forward to that day. In the meantime, word has traveled, meaning villagers have approached both me and my uncle requesting gifts. Some of these have been my own students; others include a group of six men dancing and singing in my uncle’s living room Sunday afternoon. Upon their departure, he remarked wryly that when Jesus was born, the magi came and brought gifts to Mary and Joseph, but everyone here just wants him to give them beer. Whenever someone asks me for a gift, I respond in the most forceful French I can muster, “Why? Did you carry two babies for 9 months?” and they laugh and give up. Notably, though, from house calls to gift exchanges, such events as births and death are a village matter, in terms of both who’s aware and who’s involved. Like always, these matters are delicate, a trait only compounded by where we live, making it all the more important to rejoice with those who rejoice and mourn with those who mourn.

I will be an unpaid volunteer teacher at Union Academique de Kitindi for the 2022-23 academic year. Please consider giving as you are able by clicking the button below or adressing a check to International Berean Ministries and including my name on the memo line. Donations cover room, board, and travel expenses.

International Berean Ministries

PO Box 88311

Kentwood, MI 49518-0311