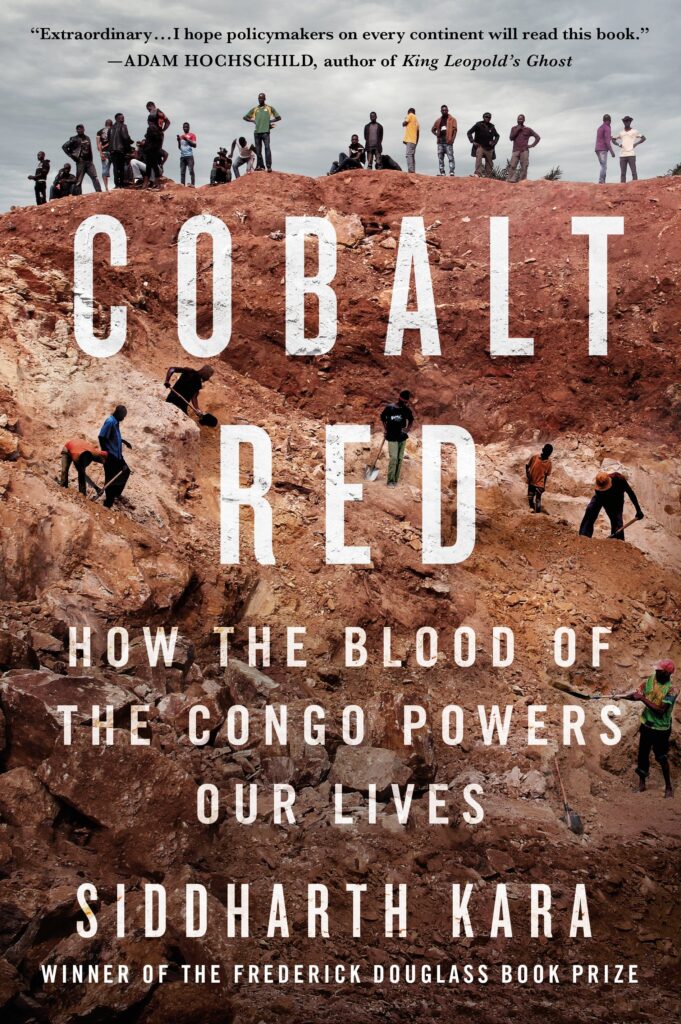

Cobalt Red by Siddharth Kara (Review)

Cobalt Red is a devastating book, an exposé on the cobalt mining industry in the southern Democratic Republic of Congo and an indictment of the global economy that makes such an industry possible. Its author, Siddharth Kara, is a writer, researcher, and activist, as well as an adjunct lecturer at Harvard and Berkeley and an associate professor at the University of Nottingham. When he is not lecturing in the US or the UK, he spends time researching modern forms of slavery around the world (his research has spanned thirty countries and six continents) and raising awareness for his findings.

Strikingly, despite the depth and breadth of his exposure to exploitation the world over, something stands out to Kara about the situation in the DRC. On page 5 of his book, he says, “…across twenty-one years of research into slavery and child labor, I have never seen more extreme predation for profit than I witnessed at the bottom of global cobalt supply chains.” I invite you to read that again, slowly. Among the tiers of exploitation Kara has been exposed to over two decades, he calls Congolese cobalt mining the most extreme.

For context, cobalt is one of the most important minerals of the 21st century. It is an essential component of most lithium-ion batteries—without it, the batteries are either less effective or less efficient. And lithium-ion batteries, along with their cobalt, are used in every major smartphone, tablet, computer, and electric vehicle on the market. That’s everything made by Apple, Samsung, Tesla, and all their competitors combined. Trillions of dollars. Lots of cobalt. Kara is quick to point out the scope of the market, as he is also quick to point out that electric vehicle (EV) batteries use ONE THOUSAND TIMES the amount of cobalt used in a phone battery and that the EV market is projected to grow by about 500 percent (that is, increase six-fold) in the next 30 years. So, the demand for cobalt, which was over 150,000 tons in 2021, is only going to grow. Unfortunately, the Democratic Republic of Congo, which produced 111,750 of those tons (72% of the global production), contains half of the world’s total supply.

Why is that unfortunate? Usually, a country’s possession of a rare and valuable resource is beneficial to its economy and people, but that has never been the case for the DRC. Congo has consistently been found to possess the hottest commodities demanded by the global market: ivory at the height of European demand, rubber right after the tire was invented, copper and other metals during industrialization, uranium during World War II and the Cold War, coltan with the development of personal computers and phones, and cobalt today. However, as Kara states, “[at] no point in their history have the Congolese people benefited in any meaningful way from the monetization of their country’s resources. Rather, they have often served as a slave labor force for the extraction of those resources at minimum cost and maximum suffering.”

In King Leopold’s Ghost, Adam Hochschild captivatingly tells the story of how a Belgian king in 1885 came to possess an area in central Africa that was 76 times the size of Belgium as, essentially, his private property. What followed was a regime of internal slave trading, forced labor at gunpoint, and murder that earned the king and Europe billions from rubber sales and destroyed local economies and livelihoods. Thousands of Congolese were directly killed with impunity and many, many more were indirectly killed because they were forced to gather rubber at the expense of their normal livelihoods. The overall loss of life as a result of the exploitation is estimated to be near 10 million people over about two decades—half of the Congo Free State’s population at the time. A higher death toll than the Holocaust.

Echoes of this past continue to ring in Kara’s account. Because the demand of cobalt is so high, because the companies using it would like to keep costs as low as possible, and because those at the bottom of the supply chain are so vulnerable, tens of thousands (including thousands of children) work for dollars (or a single dollar) a day in what Kara describes as “toxic dumping grounds.” Sickness is rampant, radioactive exposure is not uncommon, and the threat of injury or death is constant because few precautions are taken to ensure worker safety. Threats of violence also continue against the labor force, as they are, in some cases, overseen by gun-wielding soldiers who take a share of profits and are willing to shoot if disobeyed. Despite the corporate claims that those working in such conditions are working in the informal economy, Kara documents how the cobalt that children and adults extract by hand is laundered into the same refinement processes as the industrialized cobalt extraction, making cobalt mined through child labor or life-threatening methods indistinguishable as it moves up the supply chain to Apple, Tesla, Samsung, Ford, General Motors, Huawei, and BMW, all of whom get some, most, or all of their cobalt from the DRC.

Injury and death are common because of falls and tunnel collapses. In Kolwezi, the main hub of cobalt extraction in the mineral-rich Katanga province, a local told Kara that a mining tunnel collapses about every month. When collapses occur, sixty people working up to sixty meters underground can either be crushed in seconds by falling dirt and rock—killed from impact or suffocation—or, if the section of the tunnel they are working in remains intact but another section leading to the surface collapses, they won’t die instantly but will slowly lose air as the oxygen dwindles. Kara spoke to some informants who survived falls or collapses. They were deeply physically and mentally traumatized. They will never walk again and live in constant pain. Arguably, these are the lucky ones, because he also spoke with many families who had lost their husbands, fathers, and underage sons to tunnel collapses. As one informant declared, “We work in our graves.” All for $2 a day. All so phone and car batteries can last longer.

Kara succeeds in elevating local voices, analyzing exploitative systems, and noting the complexities and complicity of local corruption and of the global market. For such insight alone, the book is worth reading. But besides reporting on this information, he also seeks to invoke both empathy and a sense of responsibility from the reader. I read this book on my Kindle. I spend hours daily on my computer and phone. All these devices are implicated with “red” blood cobalt. The Congolese cobalt miners are poor people from a different culture, in a different country, and with drastically different life prospects from Kara’s audience. But Kara brings our shared humanity to the forefront, which raises questions: what if I, the reader, or my children faced what Kara’s subjects face daily? Would I accept the extreme human degradation of the current system—a system that could, by the way, change if those profiting from it took more responsibility for the wellbeing of those who are necessary for its products and profit margins? Kara compels us to consider this question and the possibility of change.

After seeing what he’s seen and comparing the work done in extracting cobalt to the places where cobalt is itself at work in every smart device and electric vehicle, he says, “The world back home no longer makes sense.” The question is whether Kara’s own advocacy can shape reality to make more sense and if readers can be convinced to join his efforts for the sake of their fellows in the DRC.

Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives was released in January by St. Martin’s Press. It can be purchased from Amazon here.

Kara, Siddharth. Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2023.

Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998.