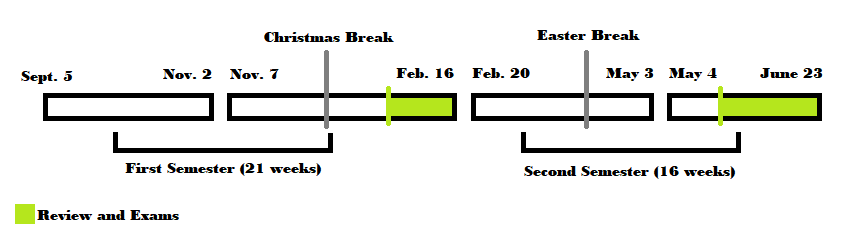

The academic year in the Congo is strange, and I’m sure our school just makes it stranger. It is determined by Congo’s Ministry of Primary, Secondary, and Technical Education and so is adhered to universally by both public and private schools across the country. It all starts on the first Monday of September, which also marks the beginning of the first of four periods that stretch throughout the year. Each semester has two of these four periods, and each period is weighted equally for grading throughout the year, not including exams (these are weighted separately and added to the total). All this seems perfectly reasonable until one takes a closer look and finds that neither the semesters nor the periods are by any means symmetrical. Instead, the first semester is 21 weeks long (excluding the two-week Christmas break), leaving just 16 weeks to complete the second semester (excluding the two-week Easter break). Even more imbalanced are the periods within the semesters: the first period is about 8 weeks, the second about 13 weeks (10 for teaching, 3 for review and exams), the third is about 9 weeks, and the fourth is about 7. Bizarrely, the fourth period includes a review week, about two weeks of final exams, a week of grading, and, finally, some exam re-take days for missed or failed exams—about five weeks in total—leaving only two weeks of actual teaching in the fourth period. If all that is confusing, below is a visualization of the calendar, but no visualization can explain why the school year has 18 weeks of teaching in the first semester and just 11 in the second, nor why all periods are weighted equally for grading when three have 8 to 10 weeks of teaching and one has just 2 weeks.

Anyway, we entered the fourth period yesterday (on a Thursday???), meaning the end of the school year is upon us. Besides this imposition of a strange schedule, an additional feature of the calendrier scolaire are numerous national holidays, including both religious and state commemorations. Among these are days to remember the deaths of political leaders, a day for martyrs, and Le 30 Avril, which is the National Day of Teaching. This year, because April 30 fell on a Sunday, there was no day off from school and the celebration was to be held on Saturday, April 29. About a week in advance of the celebration, we had a staff meeting to discuss our participation. There was also a central committee planning the event and representing the participating schools. Apparently, that Saturday would involve a gathering of all the schools in Kitindi (ten in total including both primary and secondary schools), as well as other regional schools. I heard different numbers about how many schools would be there, ranging from 17 to 27. If the schools were similar in size to ours, that could mean over 7,000 students in attendance! Needless to say, I was intrigued about how this event would go, but also wary.

My experience with large events here has not been great. Many of them suffer from three common ills: 1) poor organization and follow-through on the part of personnel, 2) lack of tools that greatly facilitate event planning, and 3) acts of nature that most events here are particularly susceptible to. On the part of the personnel, I’m not sure what to chalk the shortcomings up to. Possible reasons are the lack of a local economy or culture that privileges or equips someone to specialize in event planning, or a resigned attitude on the part of event planners due to the inability to control ills 2 and 3. As far as those go, even if someone did plan an event spectacularly, there is so much outside their control that can complique it, as we say here. For example, there are no indoor event venues any larger than a modest-sized church (seating capacity maxed at a very crowded 200). Everything takes place outside, and that means a good rain can drown even the best-planned event. And, to make matters worse, all electricity in the village is solar-powered, so a rainy and cloudy day can exacerbate ill 2, which is material lack. Many people do not have reliable means of communication, either because they don’t own phones or computers, don’t have enough money to consistently pay for network connectivity, or don’t consistently have electricity with which to power their devices. Aside from the valuable role that technology can plan in event planning itself, even communicating with parents relies on sending students home with messages written in their cahiers de communication (communication notebooks), and these have to be planned in advance—there is absolutely no way to let students and parents know about cancellations or schedule changes on a case-by-case basis. Such circumstances are surely enough to discourage even the most dedicated planners.

It turns out that our 30 Avril celebration was plagued by all three ills. Leading up to the event, our school’s participation was discussed but never followed up upon. Henry and I only had a week’s notice, so we did not have time to teach a new English song but decided to reuse an old one that we had taught the kids in March. As far as I know, no one else prepared the French songs, speeches, or sketches that were suggested in the meeting. There was also no event calendar that I was made aware of, such as something to indicate at what time and for what duration each of these allegedly 20+ schools was supposed to arrive and give their various performances. I’m not sure anyone else knew either; I think the plan was simply to show up and let the day play out as it did. Henry told me the day before that we were supposed to gather on school grounds at 8:00, and from there we’d head into town to meet the other schools.

As if on cue, it rained all Friday night and into the next morning, until nearly 10:00am. At 8:00, not a soul was on campus. I had seen this drill before. Most often it rains in the afternoon or evening here, but it seems that every time there is a big event planned, the morning of the event sees rainfall. Usually no one comes out until the rain abets, and the event is delayed about an hour. There are no cars, so all transportation happens on foot, and there is no pavement, so rain turns the road into a mudslide—no one is keen to walk any distance, let alone attend an event, in these conditions. But, even when the rain stopped, no one came to school all morning. I had honestly not been overly enthused about attending an event of unknown duration that would attempt to coordinate thousands of students and dozens of student performances. That’s not my picture of an ideal Saturday. However, I also couldn’t leave my students to perform their English song without my help, so I spent the first half of Saturday in a state of reluctant limbo, waiting to see if and when anyone would show up on school grounds. To my credit, I did try to contact the principal and the proviseur. As is typical with ills 1 and 2, the former said he thought the event was happening but he did not know when. The latter did not respond at all, presumably due to lack of connection.

It was not until after 1:00pm that the director of discipline arrived at the house and said the students were leaving for the celebration. I asked him what would happen now that the event was five hours delayed. He said he thought the students would just make a circuit through town, arrive at the designated gathering place, and be dismissed. How long could that take? An hour? I thought to myself. Of course it wouldn’t, but nonetheless, I forced myself to change into nicer clothes and to head off on the road in pursuit of our student body. The village was filled with different groups of students, probably about fifty to a hundred per group, bearing signs, singing songs, and sort of dance-marching through town in two files. All students wore the standard school uniform universal among schools here: a white collared shirt and either a skirt or pants of navy blue. I caught up to UAK’s procession about halfway through town where they were slowly making their way to the end of the village, their speed limited by the traffic of other schools in front of them. Because of the rain and delay, there were only about 25% of our students present, hardly any juniors or seniors, but those there did what they came to do, singing and dancing under the watchful eye of the director of discipline who demanded their compliance. On either side of the road, parents, non-uniformed youths, and other curious spectators gathered in small groups to watch the students dance past. They, along with my students, urged me to dance, so I attempted to mimic the basic step pattern they maintained in rhythm with their music. My performance was met with mixed responses of amusement and encouragement. All the while, the students sang pretty generic songs about Le 30 Avril. The lyrics were like this:

“We celebrate

Our holiday of April 30

Specifically, at UAK

Long live the DRC!

Long live education!

Long live UAK!”

OR, even more generic

“The 30th of April

Oh hey, oh yeah

The Day of Education

Oh hey, oh yeah yeah!”

They sound better in French, obviously.

Slowly, slowly we made our way down to the end of town and back the way we had come to the home of the village chief where he, local educational officials, and the other participating schools had gathered. In total, there were definitely not 20 schools nor 7,000 students—it was more like maybe eight schools with about 1,000 people gathered around. Greeting us all was an energetic bearded man in a blue bucket had, bright red pants, and a blue-and-yellow-striped shirt. He was speaking into a Bluetooth-equipped microphone amplified by a big speaker that was also playing distinctly Congolese music. I didn’t understand anything he was saying, but he brought the right energy and was a fitting feature of the event. As we arrived, four girls from another school were dancing in the clearing created by the gathered students as the MC hyped them up. It then became our turn to enter the space, where some of our students had their time in the spotlight.

After ninety minutes of dancing through town, our school found its place in the ring of gathered schools and waited as more schools arrived, danced, and found their places. This was followed by a singing of the national anthem and speeches in Swahili that were unintelligible to me and my students alike because of the low quality of the speaker. At this point, many students wanted to go home, but we still waited. It was now well past 3:00pm, and I know at least some of the kids hadn’t eaten all day. However, they were compliant and remained, some being afraid that the director of discipline would punish them if they left early. For my part, I bounced back and forth between the participating students and the others—juniors and seniors—who were not in uniform but had gathered on the periphery to watch the proceedings for lack of anything better to do. The worst part about the waiting was not knowing when it would end. Would we be called to sing in thirty minutes? In three hours? No one seemed to know. Surely no one else wanted to spend their entire afternoon gathered here, especially when the entire morning was occupied with ill-informed anticipation of the event itself.

Finally, around 4:30, we were called to the center to sing our song. Henry and I had taught the students to sing a version of “We Shall Overcome,” believing the content and history of the song appropriate as a hopeful anthem for the Congo in general and for our students, a resilient group of kids in ways big and small. A bonus was that the song advertised to the parents and other schools around that there was high quality English teaching at our school (some of our students also bore laptops as they danced in the streets, apparently to advertise our computer classes). It was then going on 5:00pm when the two eighth graders and one junior of my extended household said they were ready to go—they hadn’t eaten all day. Our duty done, we left the event to continue behind us and headed home as little kids parroted the lyrics of “We Shall Overcome” in the street along our way.

I will be an unpaid volunteer teacher at Union Academique de Kitindi for the 2022-23 academic year. Please consider giving as you are able by clicking HERE or addressing a check to International Berean Ministries and including my name on the memo line. Donations cover room, board, and travel expenses.

International Berean Ministries

PO Box 88311

Kentwood, MI 49518-0311

My name is Kampotela and I am very happy to read your post dear Kwabene