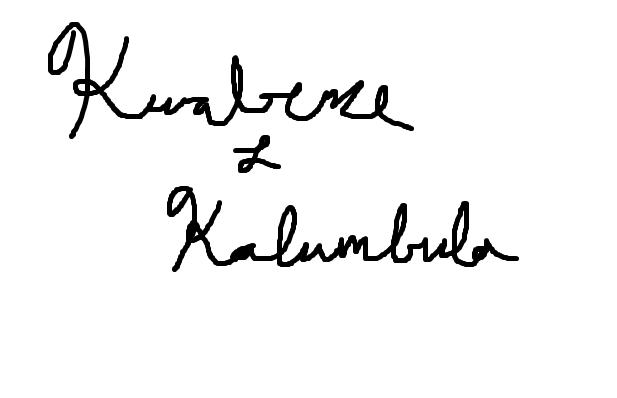

10. Kwabene Mgeni

(continuing “09. A Walk Through the Rainforest”)

…Jaden, born in 1999, is about 5’3 and relatively-light skinned with a thin beard and a wide, ready smile. He teaches in the primary school and, almost everyday, wears one of his several brightly-colored and gaudily-patterned collared shirts, a style typically more popular among the students. He also walks with a limp because both limbs on the left side of his body are slightly underdeveloped, resulting in an uneven gait. On December 6, we had each finished three periods of teaching in the morning and had the rest of the day off; it was just the opportunity we needed for me to fulfill my debt and visit his home in Walintolo.

A bit after 11:00, we set out, back on RN2 and surrounded by green. Jaden didn’t hesitate with hard-hitting questions right off the bat. The first topic of conversation concerned my marital status and aspirations. Such questions were asked of me frequently by students and colleagues alike during my first three months in Kitindi. A typical line of questioning, from either teenager or adult, flowed like: Vous etes deja marié? Non, pas encore. Mais, vous avez une fiancée? Non, non, je n’en ai pas. Une copine? Non. Mais, pourquoi vous attendez? Often these conversations are followed up with offers to help me find a wife in the village or emphatic insistence that I must marry someone from this region. Already aware of the answers to the previous questions, Jaden asked if I wanted to marry someone in Congo. I told him I’m not opposed to it, but that it would be hard given language barriers and how much our cultures and backgrounds differ—marrying someone from Kitindi would be sure to deal out two heavy doses of culture shock.

The next topic of conversation turned to the very road on which we were walking. RN2, as I’ve described before, is not in good shape. Its width varies greatly, but much of it in this section is a bit wider than a car lane and terribly uneven, full of dips and rises. In one section, there was even a massive puddle of unknown depth, full of bubbling green water—its own ecosystem. To Jaden, I expressed frustration with the road conditions; in a country with an estimated $24 TRILLION in mineral deposits, people live in poverty and national roads aren’t paved. Meanwhile, Chinese-owned or Western-backed mining operations, often partnering with nextdoor Rwanda, pay off the government for a pittance and export millions of dollars monthly. It’s not like nothing could be done about how people live here. The money is there, but the dual forces of global capitalism and corrupt and incompetent government land locals with a bad deal.

Jaden agreed with my diagnosis of the problem, including my implication of the U.S. in this matrix of profit and complicity, and his response was pointed: “Well, what side do you fall on—Congo or the US?” It’s a valid question, wrought with implications, but I answered him with what I hope to be the truth. “I’m on God’s side.” In the best French I could produce, I attempted to invoke the idea of God as not partisan to any country but soundly on the side of justice. Jaden seemed to like my response. “Et moi, je suis derrière vous sur la côte de Dieu aussi.”

It was around this time, still not far on our journey, that we noticed Augustin hastening to catch up with us. “Do you have motorcycles for legs!?” he shouted. I did, indeed, want to make good time so as not to worry my grandmother with an extended absence or be late for lunch, but we waited for him a couple minutes before continuing on. Augustin is relatively tall among our colleagues, just a bit shorter than me, and has deep dark skin, short hair, and a small bit of curly beard under his chin. He was born in 1993 and, I think, has been married twice (whether these marriages are concurrent or not, I am unsure of).

We marched on, and the conversation shifted to everyone’s other favorite topic with me: the United States of America. Jaden is awe-inspired by the U.S., or at least his idea of it. Throughout the day, when we discussed the U.S. or something related, he’d exclaim “Etats-Unis!” as if in longing or veneration. They asked about the possibility of moving to the U.S., and I tried to convey the difficulty of doing so due to visa requirements, high cost of living, and the necessity of English comprehension. They also asked if the U.S. had forests like this one, something that I’ve been asked by many people. I explained that yes, we do—that we have cities, and, beyond these, the country, and then forests that even have dirt walking paths not dissimilar to RN2. I also tried to explain, in an elementary way (in elementary French), our division of labor, with farmers and farms in the country producing so much food that they can provide for themselves and for people in the cities. We American city-dwellers can specialize in our work and make enough money to buy the food we need from farmers without having to supplement our wages by producing our own food. In Congo’s cities, of course, it’s similar, but Kitindi is a far cry from such an economy. Instead, many people, including Jaden and Augustin, subsistence farm in addition to their day jobs. This was something that I had not realized before but became apparent to me after a few ventures into the rainforest. The forest is dotted with clearings like the one with corn I had discovered the week prior, each owned and worked by a family. One might not necessarily live next to one’s own field, but most people have one, either behind their home or tucked in the forest a ways, up to a few miles from home. The wives often work these while husbands are at jobs and children at school, then the men and children return to continue farming in the afternoon. For Jaden and Augustin, this means walking the 5km back home right after school each day to work in their mashamba*.

Interestingly, when I referred to the U.S. as my home, both pushed back on this idea with an argument I’d heard before. For the Lega, nationality and home are passed on through the father, so despite 18 years in Grand Rapids, Michigan, my true home was my father’s native village, somewhere several dozen miles from Kitindi. This is also why many students insist that I must marry someone from this particular geographical area. In a similar vein, we soon encountered an older man traveling the opposite direction, pushing a bike over the road. We greeted him in French, which unwittingly launched him into a rant admonishing us for not speaking our native language of Kilega. I’d passed this man before, and he’d said the same thing, reflective of the older generations’ flagging desires that future Balega** speak Kilega.

Kilega fluency is dwindling in younger generations, but not all tradition is lost. As we neared Walintolo, talk turned to Bwami society, the Lega’s most famous institution. The Bwami (singular, Mwami) are Balega who have been initiated into a hierarchical society that touts moral principles and carries much social weight. According to Jaden and Augustin, the initiation requires the young, male candidate to go to some location deep in the jungle and stay for a month or two. Familiar with traditional rites like this but uncertain about Bwami specifics, I asked for elaboration about what takes place during those two months. Jaden himself hadn’t participated, and Augustin seemed hesitant to share specifics. I’m uncertain if this was due to the secretive nature of the tradition or to his own disposition, but I insisted I knew it must be more than simply going somewhere and staying for two months. Augustin added that the women there feed you and the elders, who speak nothing but Kilega, impart wisdom to you. Later, when we had arrived in Walintolo, I tried to press for more details, but none were forthcoming, save that 300 to 400 young men make the trip annually and there is some sort of second circumcision performed (if you’d like to learn more about the initiation rites, this brief article by Daniel P. Biebuyck, the non-local authority on Lega culture, is helpful—minus any details on circumcision).

These conversations filled the hour that it took to reach Walintolo, where we finally arrived. The village is tiny, which contributes to its distinctive calm and to its almost seamless integration with the forest. Its homes extend north and south of the road directly up to the forest’s edge on either side, and the distance is so small that both limits are easily within eyesight from the road. In terms of length, it straddles RN2, like Kitindi, but takes five to ten minutes to walk as opposed to Kitindi’s thirty. All in all, I’d guess the village is composed of hundreds or less than a couple thousand people.

Jaden’s home was on the south side of the road, near the easternmost edge where we entered the village. Between us and the house was an open-air pavilion composed of a bamboo frame and a thatch roof, maybe eight by fifteen feet. Under the roof were some low chairs and benches, and on one of these sat Jaden’s father. Jaden introduced us and I inserted a samba (Kilega for “hello”) and habari (Swahili for “how are you”) before we ducked into Jaden’s house. The house had mud walls, built by forming a lattice-work of branches and stuffing the gaps with mud; a thatch roof; and two rooms—the living room where we entered and a bedroom behind a closed door to the left. This was the second mud-and-thatch house I had been in at the time, but it seemed nicer than others; the walls were smooth and showed no signs of crack or crumble, and the fifty square foot living room featured enough wooden, benchlike chairs to accommodate about seven people around a central table. The space even had a low, bamboo ceiling between the room and the roof, which added an aesthetic feature and extra protection from the elements above. Most striking about this room, though, was the big, non-nude-but-still-erotic poster of an ethnically ambiguous Indo-European couple hanging immediately opposite the entrance. That was something completely unexpected and, in both form and content, seemed drastically and amusingly out of place.

We sat together in Jaden’s house for maybe forty-five minutes. As is customary when a guest visits, I was offered food in the form of a small pineapple that Jaden proudly presented as a product of his own field. Talk ranged from the then-ongoing World Cup to, again, the U.S. (I showed them pictures and explained the odd ceremonial dress from my graduation last year, invoking another Etats-Unis! from Jaden). Jaden’s toddler son also wandered in and out of the house but seemed uninterested in me and unimpressed with my elementary Swahili. As time passed and conversation dwindled, a large bit of the pineapple remained on the plate, but no one moved. After a while, they prompted me to finish it—I had wanted to eat it moderately so everyone could have some, but as the guest, the lion’s share was for me.

Soon after I finished the pineapple, we exited the house and made the two-minute walk to Augustin’s home. Along the way, we saw a bunch of bananas hanging from the corner of someone’s roof. “Can you eat those?” Augustin asked me. Of course I could, amused at their well-meaning hesitance to feed me something I wasn’t used to. He left the road to buy them for us as Jaden and I continued on. We soon passed a beautiful tree laden with bright, red-orange flowers and a well-built Catholic church. When I pointed it out, Jaden explained that, in contrast to the denominationally-mixed Kitindi, nearly everyone in Walintolo is Catholic, including himself and Augustin (probably should’ve guessed that one). When I tried to get at why, he said that he wasn’t sure and that I’d have to ask an elder to find out. Before long, we arrived at Augustin’s house, where I met his wife who greeted us each with a hug (the first hug I had received from a non-family member since arriving in Kitindi). We entered the house, built and arranged similarly to Jaden’s, and sat and talked some more, eating two or three bananas each.

I was prepared to go as it got to be mid-afternoon, but Jaden did not want me to leave without first meeting his wife and mother who had been off in their field the hour before. We returned to Jaden’s house where his wife had newly arrived but where his mother was still nowhere to be found. Jaden insisted that I sit and wait, so I obliged as he seemed to become suddenly busy, saying something to his wife in Swahili and ducking in and out from the back door. After a few moments I discovered why—he had parting gifts for me before I headed home. He came back into the living room holding a live, upside-down chicken in one hand and a bundle of freshly-cut, green plantains in the other. I graciously accepted his gifts, surprised by the generosity, and took one in each hand. He and Augustin kept asking, Est-ce que tu es à mesure d’aller avec tout ça? (Are you able to go with all that?) and almost insisted that they walk back to Kitindi with me, but I flatly refused to be the cause of a 10 km round trip. Instead, I said farewell to Jaden’s father and the other men who had gathered with him to sit under the pavilion, took the plantains in one hand and the chicken in the other, and headed back off into the rainforest. Jaden and Augustin accompanied me for a bit, but not for long. Seemingly satisfied with my ability to handle my cargo, they stopped after a few minutes and bid me farewell. I thanked them both very much for the visits and the gifts, then set off into the rainforest again, fuller on the return in more ways than one.

I will be an unpaid volunteer teacher at Union Academique de Kitindi for the 2022-23 academic year. Please consider giving as you are able by clicking the button below or addressing a check to International Berean Ministries and including my name on the memo line. Donations cover room, board, and travel expenses.

International Berean Ministries

PO Box 88311

Kentwood, MI 49518-0311

*mashamba: plural form of shamba, Swahili for field or farm (Ninaenda kwenye shamba langu)

**Balega: plural form of Mulega, a person of the Lega people group (Kwabene is a Mulega)

are you want wife

Hello I want wife please send how?

hello

kwabene

I am very happy when I read this post