09. A Walk in the Rainforest

For the first three months in the village, we didn’t get out much. There are a few reasons for this. First, we were busy lesson planning, teaching, grading, and job-searching for summer 2023. Second, there are not really many places worth going to; the village features a main street dotted with barber shops, cell-service stands, pharmacies, and two to three dozen small stores. Most of these stores are about 8’ x 8’ and feature a small entry space open to the street, a counter separating the customer from the salesman, and a back two-thirds of floor-to-ceiling merchandise. Each store specializes somewhat, selling charging cables and power adapters; packaged snacks and flavored drinks; alcohol; basic cooking ingredients like salt, flour, and spices; basic hardware like nails and hinges; clothing and backpacks; or toiletries and beauty supplies. It’s good to know where to find things and how prices may vary from store to store (some sell their Tanzanian-sourced soft drinks for 500 CF [25¢] instead of 1000 CF [50¢] for example), but the village proper does not really offer places to rest or recreate. Scattered throughout town, groups of men may be found drinking beer or palm wine by the roadside at any hour. Barber shops are always busy, but stores tend not to be. Shop owners and their friends will sit out under the shade of an umbrella or shadow of their storefront, talking and waiting for the off chance that a buyer wanders by. Sometimes, I have seen my students among them, either chatting with friends or waiting for customers (one of my seniors sells alcohol; three others work at family-owned pharmacies). I always go to greet them and have some small talk. However, 97% of my time is spent in the more accessible, comfortable, and familiar setting of the school grounds and home property where I interact daily with my students, colleagues, and family.

The third reason that we didn’t go out much was that my grandmother, Tati mwanumke*, strongly opposes it. She knows we lived in Chicago’s South Side for nearly four years and in Dakar, Senegal, for two months. Still, she expresses extreme concern for our safety, citing invisible and ill-defined dangers of village people and village life (including witches and witchcraft) we need to be wary of. None of these concerns are shared by anyone else, family or otherwise, yet, if questioned, she claims our lack of local language puts us at a disadvantage. Any hint of our unaccompanied absence worries her, and if she’s aware we want to leave the property, she has Dunia—her foster son and one of Henry’s eleventh-graders—or even Kisina—my father’s cousin’s son, a 13-year-old who can’t weigh more than 120 pounds—follow us. Thus went all of our initial excursions into the village. On a few occasions, we explored the commercial road, or I visited some of our colleague’s homes, and each time we were accompanied by an adolescent chaperone. However, as November turned to December, we became acclimated to our work schedules, job-hunting wound down, monotony set in, and my conscience became increasingly nagged by the need to more intentionally engage with my environment and fellow denizens. As a result of these and other circumstances, I made multiple westward ventures on RN2 and, unsurprisingly, learned A LOT along the way.

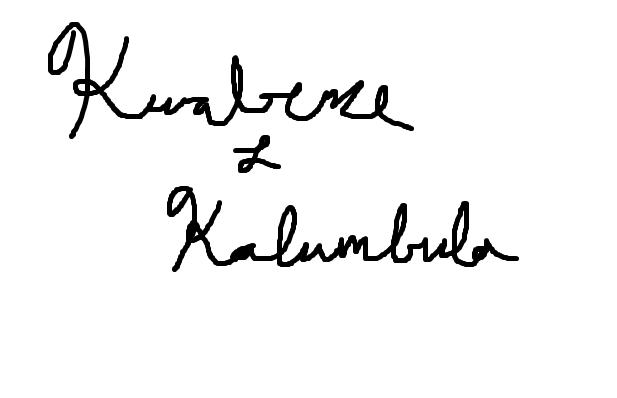

On December 1, Henry and I went for our first walk on RN2. Immediately west of our house is an extension of Kitindi, a neighborhood with its own local name. Every time I walk here, small children call out to me “muzungu!” or “Kwabene!” hoping to get a wave and alerting their family and friends to my presence. It’s impossible to go anywhere without drawing attention. I don’t actually know any of the kids, but some of them are primary schoolers at UAK. I smile and distribute waves and fist bumps as I make my way through the neighborhood. After ten minutes, one begins to exit the village and comes upon an artificial earthen dam that doubles as a narrow land bridge. The dam/bridge was built to create an etang piscicole where one can catch small, gray fish that are quite good fried. Crossing the pond, one walks up a man-made earthen stair, rejoins RN2, and truly enters the Congolian rainforest. Where there are villages, there are clearings. Inhabitants cut down wood for heat and shelter and create fields and paths and yards. However, if one goes far enough in any direction around Kitindi or any inhabited place along RN2, one encounters the jungle. Before long, one is enveloped by trees on all sides and their canopy stretched overhead.

Just as Henry and I entered this part, a motorcyclist with two passengers zoomed by. “Kizombo-fils!” one of the riders called out. That’s me, I thought but did not respond. He called back again as they continued on and I briefly left the road to take a picture. When I returned to the path, we kept walking, and Henry and I soon came upon the two passengers, dismounted and waiting for us. They urged their driver to continue ahead, which he did slowly, and they began to talk to us. I kind of just wanted to have a peaceful walk without any conversation, but meeting them proved interesting and potentially fruitful. Like most people, they have Congolese given and family names as well as French names. Frequently, when someone hastily introduces themselves, I hear all three but can only remember the French, its pronunciation being most familiar to me. These two were Jacques and Louis, and they were something like educational inspection agents. Both were college-educated (a rare find in Kitindi) and, in our brief conversation, expressed their endorsement of our work as teachers and their negative outlooks on education in the region. “You can lecture kids for hours and they won’t listen but for one minute!” Louis exclaimed. “There are teachers who didn’t master the material as students and come back to teach without knowing all the content!” Their critiques struck a chord. I’ve had difficulties getting kids to pay attention in class, let alone internalize the material. I could explain something in French, then immediately ask a student to repeat what I said, and they wouldn’t be able to do it because they were lost in their own world or talking to their friend. After about ten minutes of learning about what they do and bemoaning academic shortcomings, we caught up to Louis and Richard’s motorcyclist, whom they had apparently asked to wait for them. They invited us to visit their office in Kitindi, saying our principal would know where it is, and they hopped back on the bike and were off for an inspection the next town over.

Walking through this heavily forested section is quite pleasant. The dirt road is usually about 6 to 8 feet across, but in parts it opens up very widely, up to 20 feet. These parts tend to be in a perpetual state of muddiness, prompting the pedestrian to try to carefully pick the most solid path along the road’s margins. Either side of the road is lined with tropical trees, occasional clusters of mature bamboo stalks twenty feet tall, and a not-too-thick underbrush of ferns and other bushes. One can often see several feet into the woods on either side, and there are also sometimes paths. Curious, I followed one to see where it would lead, and after just three minutes, I came across a vast clearing surrounded by forest and populated by sparsely-planted stalks of corn amidst what I thought was a field of tall grass. I found it rather bizarre, both because of the seemingly inefficient use of space and because it was at least half a mile from the nearest home. “Guess what I found,” I prompted Henry after having returned to the road. “What?” “A big open space with like twenty stalks of corn and some tall grass. Why wouldn’t they plant, like, way more corn?” We shrugged and walked on.

We came across more clearings like the first one, similarly perplexing with their few stalks of corn and much tall grass. Many of these were directly visible from the road, and some sloped downward to reveal magnificent views beyond the fields’ edges and above the tree line. In the distance, tree-covered mountains rise to meet the clouds, varying in color on the horizon from light green to dark blue and forming stunning contrasts with the blue-gray sky. We advanced rather slowly for about two miles, stopping periodically to take pictures, look at wildflowers, or observe busy columns of ants marching as units along the road. Along the way, we encountered a clearing with about five houses where Henry saw one of his students engaged in chores in her front yard. This was an area populated by a single, multi-generational family that lived together, about halfway between Kitindi and the next village over, Walintolo. We walked just a bit beyond this, and stopped for a while to mess with a massive hivemind of reddish ants, disrupting their formation with obstacles to see how they’d adjust. This was near another cleared area off to the side of the road, this time featuring some banana trees, more tall grass, and a steep hill leading up to a crest many yards above us. “Before January is out, I’m gonna climb one of these mountains,” I said. “Imagine the view we’d have; maybe we’d even see a coltan mine or something.”

It was at this time getting on 1:00 pm, and I was scheduled to teach the teachers’ afternoon session at 1:40, so we started to head back. We didn’t get far before we encountered two of the primary school teachers on the road heading the direction we had just come from. These were Jaden and Augustin, both residents of Walintolo. They asked where we were coming from, and we explained that we were just going for a walk. Then, Jaden accused, “You lied to me, Kwabene. You said you would visit us in Walintolo, but you haven’t come.” I was at first thrown off by the forwardness of his words, but, recognizing the need to both get out more and to pacify him, I agreed to be their guest soon. We waved goodbye to them and trudged on, now with greater haste so that I could make the afternoon session. On the way back, we passed more students we knew, heading home after school. A number of students and, I think, five teachers live in Walintolo and have to make the 6-mile round trip, rain or shine (either can be burdensome, depending on the day) to attend school. We got back to school grounds in time for me to teach and without detection from Tati mwanumke. It had been a good excursion and, unbeknownst to me, foreshadowed much more good to come from ventures westward. (To be continued…)

I will be an unpaid volunteer teacher at Union Academique de Kitindi for the 2022-23 academic year. Please consider giving as you are able by clicking the button below or addressing a check to International Berean Ministries and including my name on the memo line. Donations cover room, board, and travel expenses.

International Berean Ministries

PO Box 88311

Kentwood, MI 49518-0311

*this is what I’ve called my grandmother all my life; it literally translates to “woman grandparent” in Congolese Swahili

I like how you offer real-world insights into subjects that are topical and popular.