Defending Baumbach's White Noise: Why It Is How It Is (7/10 Movie Review)

I was recently on vacation from my day job teaching English in a rural Congolese village, so I allowed myself the freedom to (overly?) engage in film and best-of-2022 talks that I might have otherwise placed more limitations on. Searching for something to watch last week, I happened upon White Noise, a late 2022 release from acclaimed writer/director Noah Baumbach (Frances Ha, Marriage Story) and the increasingly mainstream, auteur production company A24. I thoroughly enjoyed the movie and thought it was somewhere between good and great. However, I was surprised to discover that the film seems to be polarizing, underrated, and unfairly criticized by audiences and critics alike. I think these criticisms are based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the film as an expression of postmodern thought and art, which I hope to explain here.

Some of the criticism claims there’s something lacking in the movie’s emotional tone. Max Cea from Esquire asks “what went wrong with White Noise”, claiming the film is emotionally disconnected and that the two main protagonists “inflect their speech with a dry, melancholy affect that’s a little too cute to have much emotional resonance.”1 Additionally, further critique accuses the film of being overfull with disappointing payoff. A.O. Scott at the NYT says “there is something detached about the film, a succession of moods and notions that are often quite interesting but that never entirely cohere.”2 Collider’s Brian Formo gives a C+ rating, decrying the film as being “guilty of what it criticizes: too much.”3 Interestingly, critics nearly universally praise Baumbach and his team for the technical and aesthetic achievement of White Noise, which is truly grand. For them, the issue lies in the script—both its message (or lack thereof) and presentation—and here, I think, lies their misunderstanding.

I think these critics lose sight of the point of White Noise, which I began to piece together after I discovered that it has a source text. Full-disclosure: I personally have not read Don DeLillo’s 1985 novel of the same name, so I cannot speak to critiques on the basis of the text. However, the book is considered a classic of postmodern literature, replete with philosophical musings and commentary, and, from what I can gather, the film is a valiant effort to be faithful to it. Many critics acknowledge that the film is an adaptation without themselves referring to the source material, noting simply that it is both universally loved and notoriously unfilmable. One exception is Vox’s Alissa Wilkinson who, while echoing some of the critiques, understands White Noise much better than others and gives a positive review with frequent reference to the book.4

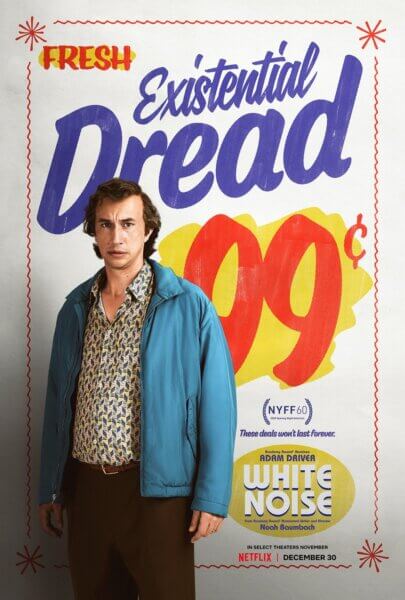

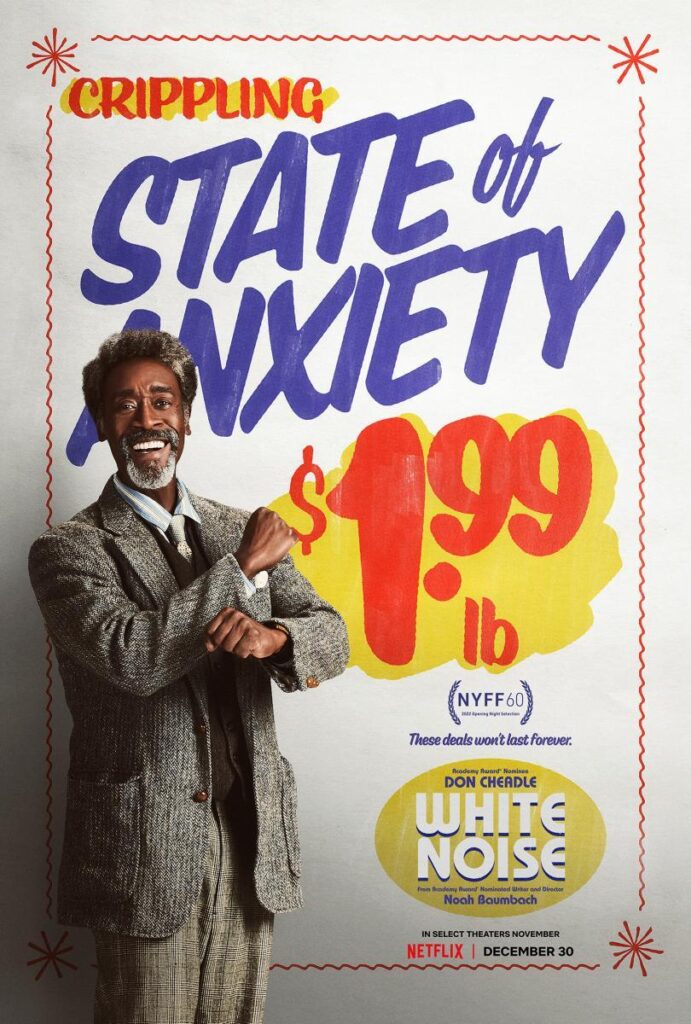

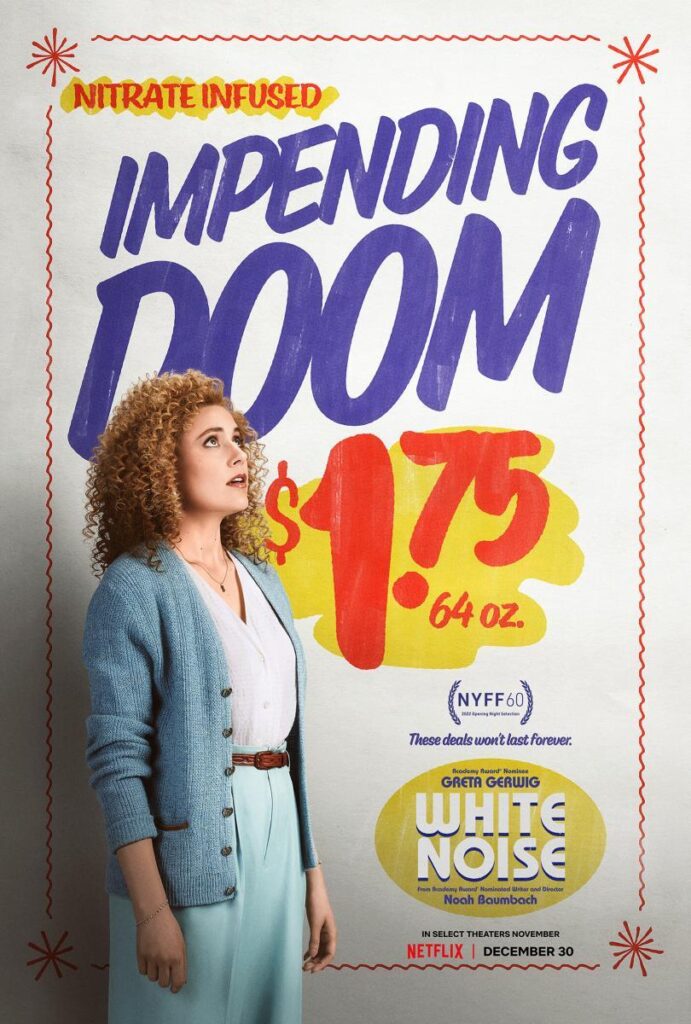

So, what is White Noise? The film centers around Jack Gladney (Adam Driver), a middle-aged professor and renowned founder of the field of Hitler Studies, who lives in the suburbs with his family. His wife Babette (Greta Gerwig) is a homemaker who also teaches evening posture classes to the elderly at a local church. Their family is composed of four children/stepchildren, each from a different marriage, who bring a constant buzz of activity and esoteric conversation to the household. Rounding out the main cast is Murray Siskind (Don Cheadle), a colleague of Gladney’s at the College-on-the-Hill who studies American culture and hopes to emulate Gladney by founding the field of Elvis Studies.

The film is divided into three chapters, the first of which introduces us to its tone and characters. In Jack’s home, three different conversations transpire at once as Jack, Babette, and the kids throw out information and respond to one another in a confusing cacophony of semi-relevant facts. We also observe Babette showing signs of forgetfulness, raising the concerns of the eldest daughter Denise (Raffey Cassidy) who discovers that her mother has been secretly taking an off-market drug called Dylar. And, at night, Jack is haunted by dreams featuring a mysterious figure, highlighting his ever-present but repressed fear of death. At the College-on-the-Hill, the movie satirizes American academia, both as professors converse over lunch and as Siskind and Gladney dramatically and pseudo-intellectually lecture to a room of students about Hitler’s and Elvis’ respective relationships with their mothers and their trajectories toward death. Finally, we are introduced to the supermarket, where Jack and Murray shop together, marveling at the fancy new butcher shop as we, too, marvel at the utopian feel of the store’s bright colors, familiar 80’s branding, and pristine and fully-stocked shelves (brilliantly executed set design credit to Production Designer Jess Gonchor and Set Director Claire Kaufman).

The status quo is interrupted in chapter two when an “Airborne Toxic Event” occurs, sending the family into a panic and bringing the prospect of his death nearer to the forefront of Jack’s mind. As the film progresses, we also learn about Babette’s own crippling fear of death and its relation to her secretive self-medicating. The movie climaxes as the fallout of the parents’ struggles unravels, all while the film continues to wrestle with and poke fun at the postmodern condition. Without giving too much away, I can understand why some may feel it ends unsatisfactorily. The ending features a soliloquy by an atheistic German nun who does not believe in heaven, hell, or God but simply commits herself to the common good by working in a hospital and helping maintain the facade of the spiritual. She essentially exhorts Jack and Babette to live similarly, the sun rises, and soon thereafter, the film ends. However, I think this is an intentional move which underlines the film’s key explorations.

The film is accused of being emotionless and filled with sights, sounds, and information without real resolution. However, given that the 1985 White Noise is a classic of postmodern literature, this may very well be the point. Postmodernism, an artistic and philosophical movement emerging in the mid-twentieth century, is true to form in that it is difficult to define. I say “true to form” because my own working definition for postmodernism is the mode of thought—and of being—which is skeptical of definite answers, ultimate truth, and perfect prescriptions for what to believe and do. Modernism asserted that there are ideal forms and infallible solutions, inspiring authoritarian political projects, an obsession with geometry in art and architecture, and the pursuit of perfection in science and society. However, postmodernism rejects the notions underlying modernism, leading to breaks with convention and challenging much that was taken for granted. Political, social, religious, and artistic norms were questioned and, by some, abandoned. Postmodernism brought, in some senses, liberation; however, it effected, also, an unmooring and a new constraint on the postmodern soul—that caused by a deep-seated uncertainty and insecurity.

It is difficult to discuss cultural postmodernism without also considering neoliberalism, another challenge to modernism that emerged largely in tandem with postmodernism. In the realm of governance and economics, it, too, rejected authoritarianism by unmooring the market from the state. However, like its philosophical cousin, neoliberalism brought with it new constraints, in this case being the control of the market over the individual. In the words of journalist Stuart Jeffries in his (very good) 2021 book on postmodernism:

“Both post-modernism and neo-liberalism were couched in terms of liberation—the former from the tyranny of functional style, the latter from the state. And yet, the new neoliberal orthodoxy of minimal state and personal responsibility substituted one tyranny for another—namely the tyranny of the market…Post-modernism’s role in establishing this new tyranny was to extend that narrative of liberation into culture, to suggest that, instead of modernism’s constraining rulebook, we were now in a free-for-all where anything goes.”5

White Noise is, at its core, a story about the fear of death, yet it reflects postmodernism and neoliberalism in how it deals with this struggle and how it portrays the world its characters are situated in. Postmodernism is marked by questioning, and this is exacerbated by constant streams of new: new information as science and philosophy progress, new technology that solves old problems but creates new ones, and new things to buy and consume as markets and wealth grow. In the postmodern age, we have more information than ever before but also more questions; knowledge doesn’t bring us closer to an end point as modernism posited but, instead, just gives us more to consider. This is overwhelming, and leads us to one of two directions: trying to keep up by continually questioning and analyzing new information, or resignation to the bombardment and simply trying to cope, often through consumption of various forms.

The film portrays both responses to postmodernism in the three primary loci of the family, the university, and the supermarket. At home, the children produce continuous streams of facts and the TV or radio is almost constantly on. Mass media fueled by commercialization offers something both to those engaged and those resigned; it provides both information and spectacle. The film observes that the former drives consumers to the latter in a sort of positive feedback loop. In the words of Jack’s colleagues, piling on comment after comment:

Prof 1: “It’s natural. It’s normal that decent, well-meaning people would find themselves intrigued by catastrophe when they see it on TV.”

Prof 2: “We’re suffering from brain fade.”

Prof 1: “We need an occasional catastrophe to break up the incessant bombardment of information.”

Prof 3: “The flow’s constant. It’s words, pictures, numbers…”

Just as television contributes to the problem, it itself offers a solution by providing entertainment and spectacle through which one can cope. So, too, does the supermarket, the quintessential picture of neoliberal consumerism and mind- and body-numbing excess. For their part, the university and its academics represent engagers, as seen through their pursuit of knowledge and faux-intellectual cafeteria dialogues. However, with the spectres of their deaths haunting them, Jack and Babette are more like resigned copers. Jack often lacks the ability to reckon with reality, whether this pertains to the Airborne Toxic Event, his wife’s drug problem, or the inevitability of his own death. For Babette’s part, her resigned coping comes by the mechanism of medication. And both, I think, display this numbness in their speech and mannerisms. From the very beginning, whether discussing life or death, expressing love or hurt, the spouses speak in a sort of matter-of-fact tone and somewhat elevated prose. It can come off as odd or unrealistic or emotionless, but I’d argue that this is exactly the point. The world of White Noise is a fantasy, a portrait and a parody of postmodern thought, which deals with postmodern questions through postmodern means. Its characters are all either copers or engagers, and their world is one that pushes its inhabitants to one of the two extremes. Whether it be from fear of death or from streams of information, the bombardment must be coped with or engaged with, and either option necessitates some emotional distance.

Ultimately, I think the film’s explorations of the postmodern condition are expressed in both its content and its presentation. The film is accused, on one hand, of lacking emotion. On the other hand, it is said the film includes too much without sufficient resolution. However, a postmodern world suffers from exactly these things. The film explores this by commenting on it but also by itself being overfull with unresolved ideas and conversations; in so doing, it can make us feel the very overstimulation and futility its characters feel. The constant information and questions and consumption of postmodernism are overwhelming to the point of being numbing, and, while everything is presented as important through eloquence or shiny packaging, this is not necessarily the case. Instead, there are no satisfactory answers in the end, and neither science nor wisdom can save us from death. In the age of postmodernism, all there is is white noise and the need for something good to cling to, which could be family, humanitarian service, an academic department, or whatever else you’ve got.

To keep up with what I’m watching, follow me on Letterboxd here! White Noise premiered at the Venice International Film Festival and is currently streaming on Netflix. IMDB: 5.7, Rotten Tomatoes: 63%

References:

1. Cea, Max. “What Went Wrong with White Noise.” Esquire, January 2, 2023. https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/movies/a42378178/white-noise-netflix-adaptation-review/

2. Scott, A.O. “‘White Noise’ Review: Toxic Events, Airborne and Domestic.” The New York Times, November 23, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/23/movies/white-noise-review.html

3. Formo, Brian. “‘White Noise’ Review: Noah Baumbach’s Satire is Too Busy for Its Own Good.” Collider, December 30, 2022. https://collider.com/white-noise-review-noah-baumback-adam-driver-greta-gerwig/

4. Wilkinson, Alissa. “White Noise, Noah Baumbach’s new Netflix movie, explained.” Vox, December 30, 2022. https://www.vox.com/culture/23521022/white-noise-netflix-baumbach-explained

5. Jeffries, Stuart. Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern. (New York: Verso Books, 2021), 14.