08. To Be Sick in Kitindi

PART ONE: ONSET

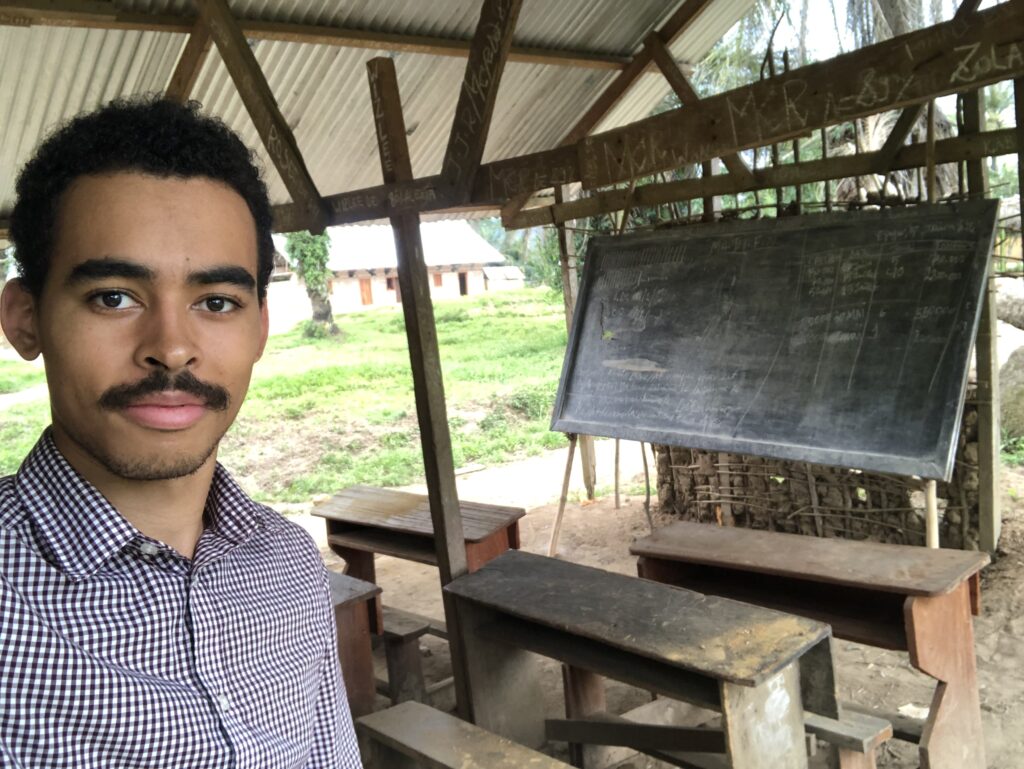

I began to feel sick on Monday, October 31, but at first it was so minor that I barely noticed. It typically reaches 80° F each day here, but in the mornings it can feel pretty cool, especially if you aren’t dressed for it. Well, I felt a bit cool around 9:00 am that Monday morning, and Veronique, one of my seven 9th graders taking Correspondance Commerciale Anglaise (or COCOA) took notice. “Prof, tu es malade?” she asked. I said I wasn’t sick, just a little cold, and told her to get back to copying notes off the board. She was right, though—it wasn’t just a morning chill—and I told her so by Wednesday.

At first the only symptoms I noticed were chills, and I taught through them. That week was the last week of the first period and ended on a Wednesday so that teachers would have time to calculate the first period grades. I planned to grade a bunch of homework and quizzes, tally up points for the first period, and also use the long weekend to flesh out all my lesson plans up to the end of the second period. By Thursday, though, the chills were getting worse and were joined by muscle aches, headache, weakness, and a low appetite. I managed to finish the period’s grades, but I didn’t have the strength to get anything else done that weekend. I hoped to rest through the weekend until the “flu” passed and I had recuped my strength to teach Monday. A nurse named Espoir (French for “hope”) came over the weekend to prick my finger for a malaria test, and that came back negative. At the same time, the aching symptoms started to go away, so I was sure the flu was receding, and I assured everyone as much on Sunday and Monday. Due to my absence from church Sunday, two members of the pastoral staff came to pray for me each day, and I thanked them and told them I thought it was almost through.

But I missed another day of teaching on Monday, and, despite no more aches, the chills and weakness did not go away. On Tuesday the 8th, I tried to teach again, and it did NOT go well. I felt weak and unsteady, my eyes weren’t adjusting to light properly for some reason, and twice I stood up too fast while teaching and my vision blacked out for five seconds. Not good.

PART TWO: ALARM

Despite wanting to avoid the village hospitals at all costs (what better place to catch something my body’s never encountered before?), I decided I should talk to someone with local knowledge who could give me a diagnosis. My uncle recommended Dr. Patrick (French pronunciation), and my grandfather and I hired a motorcyclist to take us across town to the hospital where the man who I believed to be the sole physician of Kitindi works (I have recently heard that there might be more, but this is what I believed then). The hospital is in very rough shape—it is composed of a cluster of single-storey buildings, the first of which is roughly built with a floor that might have been cement or stone but was so covered in dust that it looked like a dirt floor. I’m not sure of the building’s electrical capacity (I saw a few bare, dusty bulbs), but no lights were on while we were there. The hallway was dark, and the rooms were lit by sunlight entering through open or partially open windows. From what I saw, this main building had a single narrow hallway that included two rooms on the left and opened in the back and to the left into a third larger room. It was hard to tell what was to the right, but I recall seeing mostly wall which at some point opened into a big, dark open space, the purpose of which I could not discern. I think the first two rooms on the left were for receiving patients, while the third room included a table, a dust-stained cot, and shelves and shelves of white cardboard boxes with various medicines.

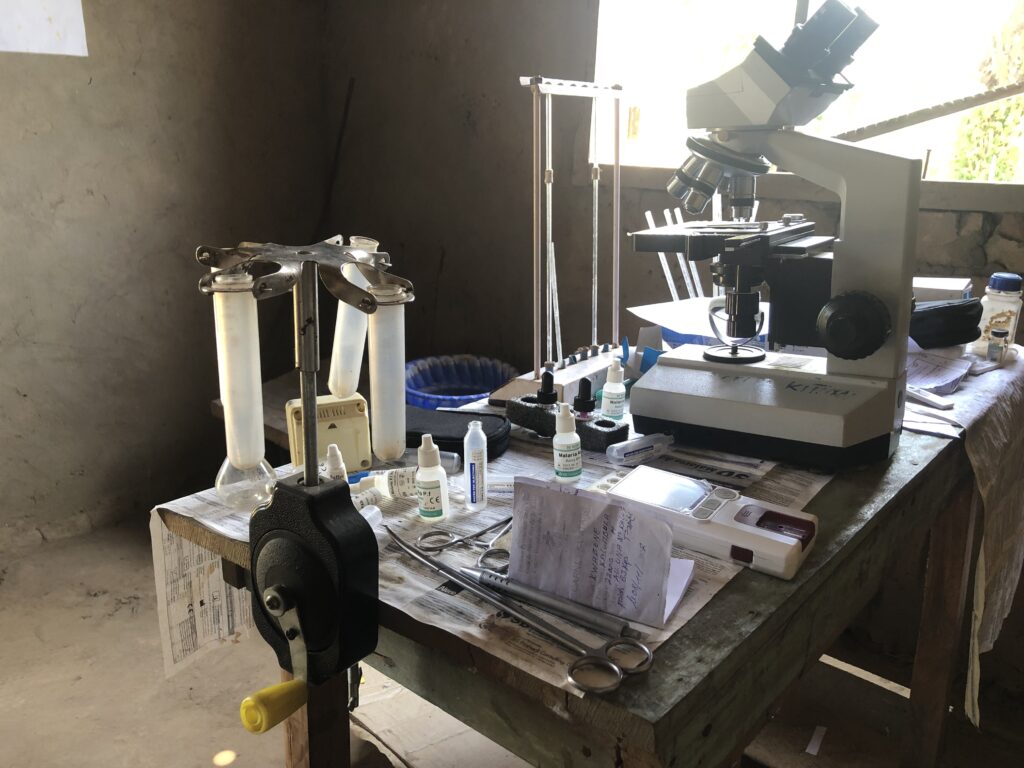

We started in this room, where my weight and other characteristics were recorded, then we followed the doctor into one of the receiving rooms where he asked for my symptoms, checked my internal organs, measured my blood pressure (it was pretty low), and looked at the whites of my eyes. He next sent me off to a small, separate, two-room building, one of which included a decent-looking microscope and a hand-cranked centrifuge. Here, my finger was pricked again for blood, yielding another negative malaria test as well as two other negatives for things I didn’t catch. Finally, we rejoined Dr. Patrick where he considered the facts and gave his diagnosis: typhoid.

I bought the medicines he prescribed, but I did not believe I had typhoid. For one thing, I was vaccinated against it last year, and additionally, I had not had stomach problems, and I trusted the cleanliness of my food and water. But if it wasn’t typhoid, what could explain the low blood pressure and the constant, unending cold? That was by far the worst symptom. In a series of WhatsApp messages to my mother that night, I told her:

No more pain, but still cold

And it is such a cold, piercing bone and cloth

Rattling chains

Icy streams

The vast expanse of space

I was really cold. I didn’t want to overreact if it was just a lasting flu, but I also didn’t want to neglect some unfamiliar tropical illness that might have complications and quickly take a turn for the worst. I started to worry about the possibilities, and that’s when I made a terrible, terrible mistake: I began researching my symptoms online.

Within seconds, I was bombarded with articles foretelling my imminent death. “Muscle aches? Persistent chills? Low blood pressure? You better be sure you’re not dehydrated, or your organs could fail at any moment. Do you have a fever, too? Add a three-day fever to these symptoms, and you’ll require medical attention IMMEDIATELY. I don’t want to sound pessimistic, but if you don’t get to a doctor soon, I give you three, maybe four days to live.” Needless to say, I was slightly concerned and began self-diagnosing to compensate for Dr. Patrick’s oversight.

I don’t get sick very often, and I’m not usually quick to go to the doctor. If something seems off, I tend to think it’s not too bad and will resolve itself. This strategy doesn’t always work, like the time when I assumed my broken finger was just jammed and didn’t have it checked until I had already played 80% of a basketball season. But, perhaps to save myself the time, money, and embarrassment of overreacting, I’m slow to seek medical help. And, because I am rarely sick, I don’t quickly do the things one might normally do right away, like checking my temperature. After reading about how often fever and chills go together and seeing the exhortations of online medical websites to call a doctor if a high fever lasts three days, I decided to check my temperature. It came in the first time at 103.6° F, which, in retrospect, might have been a low reading and was a temperature I maintained for who knows how long.

At this point, my concern reached its peak. What I had read put me on edge, especially because many of the possible diagnoses I found considered time as a factor, claiming the longer I was sick, the more danger I was in and the more important medical attention was. When I first checked my temperature, I was eleven days in. This was of some concern for me, and the reactions of people I was talking to didn’t help much on this front. Additionally, given the lack of medical infrastructure in Kitindi, seeking more serious help would require a two day’s land journey or a very hefty bush plane price to Bukavu (where, even then, the quality of medical care remains unknown to us). Adding to the worry about possible health complications was the distressing conundrum of whether leaving the village and the school for an undetermined period of time was worth it financially or would even make a difference for me health-wise anyway. Given so much uncertainty, it was a question which no one seemed able to answer.

PART THREE: HOPE

My dad helped me get in touch with various healthcare personnel in the U.S. via Zoom who couldn’t really give a diagnosis but still assured me I wasn’t dying despite what the internet said. They also encouraged me to drink more water and take both the antimalarial and antibiotic medications at my disposal. For about two days I took these, but my fever remained, at which point my grandfather insisted I undergo intravenous malaria treatment.

At first I was hesitant, doubting whether I truly had malaria in the face of two negative tests, and also not particularly wanting to be rendered immobile with a needle stuck in my arm for hours on end. However, at this point my grandfather was taking things into his own hands. He invited a nurse to the house, who assessed the situation. It was Espoir again, and he repeated that malaria is endemic to this region and that I could still have it, even with two negative tests. So, I began his treatment regimen.

On the morning of Sunday, November 13, I had a temperature of 102.3°. That afternoon, Espoir returned to set up an IV drip bag, and I began about four hours of treatment for both dehydration and malaria. I still felt chills that night, but by Monday morning, my fever had decreased three degrees and never went up again after another eight hours on the IV. For his part, Espoir was sitting in the livingroom with me or outside the house for probably 50% of the time I was hooked up, switching treatments, injecting quinine directly into the needle contraption in my arm, and monitoring me while I mostly sat there and read or texted. After the second day, I felt quite well, and I credit it almost entirely to his care. On Tuesday, he came again to deliver ampicillin directly into my bloodstream. Each day he came, he’d ask me how I was doing, answer questions, and dutifully stay nearby, sometimes for hours. It was pretty serious care, and I feel like I pushed the village’s medical capabilities to their limits. In the end, it took just two days of his treatment for the fever, chills, and loss of appetite to go away. It turns out Espoir had been right; I had malaria after all.

It’s a running joke that no matter what someone has, doctors in regions like this will diagnose you with malaria. I think this is due in part to the commonness of the symptoms and the lack of robust diagnostic tools. However, I learned from this experience that malaria is so endemic, and difficult to actually detect with a test, that treating it anyway is actually a pretty safe bet. Many Africans (Central, West, East, and South) get malaria several times throughout their lives. It is so common that there were about 229 million cases in Africa in 2020, meaning about 20% of the entire continent got it in just one year (World Health Organization, 2022). Malaria is considered deadly; however, of these many millions, only about .3% actually died, the majority of these, unfortunately, being children under the age of five, and many of these being in Congo (about 13% of the world’s malaria deaths happen here).

Ultimately, my life was likely not in danger, though there are occurrences where malaria drastically worsens and can kill within a day. However, it is no longer as deadly as it once was, and, fortunately, it is no longer a leading cause of death for children in sub-Saharan Africa (WHO Africa, 2016). It is easily treatable (if one has financial and geographical access to treatment), and can be prevented, especially with bed nets. From 2000 to 2016, malaria deaths in sub-Saharan Africa decreased by 66%, and a lot of this trend is attributed to mosquito nets and increased testing. Intentional efforts have been driving these improvements, and WHO and others are continuing work to prevent and treat the disease, aiming for a 90% reduction in both incidence and mortality by 2030 (World Health Organization, 2022).

Some advice for someone who finds themselves with malaria in a central African village: know who and what to pay attention to. Malaria can be serious, and a fever lasting too long is not good. So, when someone like Veronique says something like, “if you’re the only one cold then you’re probably sick,” maybe pay attention, and maybe check your temperature, too. And, when someone with local expertise like Espoir gives a negative test but says, “yeah, you probably have malaria anyway,” maybe he’s onto something. When possible, identifying and treating things early are key so things don’t get complicated and you don’t become dehydrated and possibly, possibly, on the verge of organ failure like I was. And, finally, watch out for WebMD—people die from malaria and fevers, but the odds really are that you won’t. Identify your symptoms, use the internet to note some possibilities, and consider your context and local knowledge to determine what’s probable. If you monitor and treat early, you’ll likely resolve the issue in a timely manner and will be able to skip altogether the stage of doom-reading premature pronouncements of your impending demise.

I will be an unpaid volunteer teacher at Union Academique de Kitindi for the 2022-23 academic year. Please consider giving as you are able by clicking the button below or addressing a check to International Berean Ministries and including my name on the memo line. Donations cover room, board, and travel expenses.

International Berean Ministries

PO Box 88311

Kentwood, MI 49518-0311

We are praising God for His faithfulness. His unfailing love endures forever. Thank you for this report and may the Lord keep you and your coworkers as we begin this week of advent. I am grateful to Espoir, the medical treatment team in Kitindi and the many doctor friends who responded to our pleas for help. May the Lord bless and keep you!

Praise God you are on the mend and for the wise people around you to lead the efforts to get you well.